SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA, UKRAINE,

AND NATO

|

|

DR. ERIC ENGLE*

|

|

|

INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................

|

99

|

|

I. THE COLD WAR ..........................................................................................

|

100

|

|

A. Marxism..............................................................................................

|

100

|

|

1.

|

Marxist Economic

Theory.............................................................

|

101

|

|

2.

|

Marxist Legal

Theory....................................................................

|

103

|

|

B. The Soviet Union

................................................................................

|

104

|

|

1.

|

Soviet

Law.....................................................................................

|

104

|

|

|

a. Antinomianism in Soviet

Law..................................................

|

104

|

|

|

b. Human Rights to Soviet Law

...................................................

|

105

|

|

|

c. The Soviet State

.......................................................................

|

107

|

|

2.

|

Soviet

Economics..........................................................................

|

109

|

|

|

a. The Planned Economy

.............................................................

|

109

|

|

|

b.

Autarchy...................................................................................

|

110

|

|

C. The Cold War .....................................................................................

|

112

|

|

II. FROM COLD WAR TO COLD PEACE ...........................................................

|

114

|

|

A. Economic Collapse

and Corruption ...................................................

|

114

|

|

B. The Commonwealth of Independent

States (CIS) ...............................

|

115

|

|

C. The Eurasian Economic Community

(EurAsEC) ...............................

|

118

|

|

III. THE COLD PEACE .....................................................................................

|

119

|

|

A. Differences Between the Cold War

and the Cold Peace ....................

|

119

|

|

1.

|

A Market Economy

.......................................................................

|

119

|

|

|

a. Trade (Resources)

....................................................................

|

120

|

|

|

b. Investment

(Sanctions).............................................................

|

123

|

|

|

c. Sanctions

..................................................................................

|

124

|

|

|

d. The Energy Weapon?

...............................................................

|

127

|

|

2.

|

Democratic

Legitimation...............................................................

|

129

|

|

3.

|

Market Economy

...........................................................................

|

130

|

* Dr. Jur. Eric Engle J.D. (St. Louis) DEA

(Paris II) LL.M. (Humboldt) was a Fulbright specialist

(Ukraine). He can be reached at eric.engle@yahoo.com. His

works can be seen at: http://papers.

ssrn.com/sol3/cf_dev/AbsByAuth.cfm?per_id=879868.

Dr. Engle wishes to thank the Fulbright foundation for

supporting this research and the editorial team at the St. Louis University Law Journal.

|

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

|

|

98

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

|

B. Similarities Between the Cold War

and the Cold Peace

|

.................... 130

|

|

1. Ideology: Great Russian Orthodox

Corporatism in a Clash of

|

|

|

Civilizations

..................................................................................

|

131

|

|

|

a. Great Russian, Nationalist,

Inclusive, Expansive.....................

|

131

|

|

|

b. Orthodox

..................................................................................

|

133

|

|

|

c.

Corporatism..............................................................................

|

135

|

|

|

d. Clash of Civilizations

...............................................................

|

138

|

|

2.

|

Authoritarianism: “Vertical Hierarchy”

........................................

|

139

|

|

|

a. The Concept of

Law.................................................................

|

140

|

|

|

b. Corruption

................................................................................

|

144

|

|

|

i. Corruption as a Governance

Strategy..................................

|

144

|

|

|

ii. Political Prisoners and

Amnesties.......................................

|

148

|

|

|

c. The Patriarchal Family

.............................................................

|

150

|

|

|

i. “The Family” and the Orthodox Church

as Quasi-State

|

|

|

Corporatist Institutions in Russia

........................................

|

151

|

|

|

ii. “The Family” as a Quasi-State

Institution: Inter-Country

|

|

|

Adoption..............................................................................

|

154

|

|

|

d. Civil and Political Rights

(Bürgerrechte).................................

|

155

|

|

|

e. Human

Rights...........................................................................

|

159

|

|

3. International Law and Foreign

Policy: Geopolitics and “Clash

|

|

|

of Civilizations”

............................................................................

|

161

|

|

|

a. Trade Policy

.............................................................................

|

161

|

|

|

b. Rearmament and Arms Sales

...................................................

|

162

|

|

|

c.

Terrorism..................................................................................

|

163

|

|

|

d. The Use of Force Under International

Law..............................

|

164

|

|

|

i.

Georgia................................................................................

|

168

|

|

|

ii. Syria

....................................................................................

|

168

|

|

|

iii.

Ukraine................................................................................

|

170

|

|

CONCLUSION...................................................................................................

|

172

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

99

|

INTRODUCTION

The Cold War featured constant covert

conflicts, such as terrorism and proxy wars ranging “from one

end of the globe to the other.”1 These

conflicts repeatedly threatened to erupt into overt (nuclear)

warfare. Russia and NATO are on the edge of a new cold war

because of the illegal annexation of Crimea2

and more than a half dozen other issues, such as Syria,3 gay rights,4 Magnitsky

list,5 et cetera. I call the current

situation a cold peace. This cold peace features isolated and

exceptional regional conflicts as opposed to the systemic global

conflict that was the Cold War. Furthermore, there is much less

state- sponsored terrorism in the cold peace than occurred in

the Cold War. Consequently, exceptional regional conflicts such

as Ukraine, Georgia, and Syria may be manageable but must be

understood as occurring in an asymmetric field, with zero-sum

outcomes regulated more often by politics than by law. Although

positive-sum outcomes remain possible in economic

relations, they have become less likely due to Russia’s illegal

annexation of Ukraine.6

Consequently, Russia will most likely be

increasingly isolated politically and economically, and Russian

foreign relations will be increasingly zero-sum or

even negative-sum. However, Vladimir Putin and

Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s President and Foreign Minister,

respectively, are both rational actors and are not in fact “[i]n

another world.”7 They pursue the

Russian national interest following a realist theory of

international relations.8 United

Russia has crafted a coherent narrative and implements an

alternative ideology that allows it to challenge global liberalism—to

the detriment of the rule of law and protection

1.Aaron

David Miller, Five Myths About the

Ukraine Crisis, CNN (Mar. 14, 2014, 6:00 AM), http://www.cnn.com/2014/03/08/opinion/miller-five-myths-about-ukraine-crisis/.

2.See

Fred Dews, NATO Secretary-General:

Russia’s Annexation of Crimea Is Illegal and Illegitimate, BROOKINGS (Mar. 19, 2014, 2:49 PM), http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/brookings-

now/posts/2014/03/nato-secretary-general-russia-annexation-crimea-illegal-illegitimate.

3.Holly

Yan, Syria Allies: Why Russia, Iran and China Are

Standing by the Regime, CNN (Aug. 29, 2013,

9:01 PM), http://www.cnn.com/2013/08/29/world/meast/syria-iran-china-russia- supporters/.

4.Russia:

Anti-LGBT Law a Tool for Discrimination, HUM. RTS. WATCH (June 30, 2014), http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/06/29/russia-anti-lgbt-law-tool-discrimination.

5.Michael

R. Gordon, U.S. Imposes New Sanctions on 12 Russians, N.Y. TIMES, May 21, 2014, at A8.

6.Dews,

supra note 2.

7.Contra

Peter Baker, Pressure Rising as

Obama Works to Rein in Russia, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 3, 2014, at A1

(quoting Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany). Anne Applebaum

wondered aloud whether Putin might be irrational: “[U]nless

Russian President Vladimir Putin suddenly becomes irrational—which,

of course, can’t be excluded—he must know that a full- scale invasion is entirely

unnecessary.” Anne Applebaum, Russia Puts on the

Squeeze, WASH. POST, Feb. 28, 2014, at A17.

8.RICHARD SAKWA, PUTIN: RUSSIA’S CHOICE 267 (2d

ed. 2008).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

100

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

of human rights. Russia presents a real risk

to the global rule of law due to domestic corruption and

international lawlessness, as most recently seen in Ukraine in

Donetsk and Crimea, but also in Georgia and the various “frozen”

conflicts in other former Soviet Republics (Moldova, Azerbaijan,

and Armenia).9 However, that

challenge is regional, not global, and cannot become global

because Russian ideology is involuted and unattractive.

Furthermore, though rational actors, President Putin and/or

Foreign Minister Lavrov overestimate Russia’s power and

possibilities and underestimate the resiliency of NATO Member

States.

To reduce the risks of a new cold war with

rampant proxy wars and state- sponsored terrorism and to

effectively foster the rule of law, the protection of human

rights, and democratic internationalism, NATO Member States must

recognize the exact nature of the challenge with which they are

confronted. A proper appreciation of Russia’s real strengths and

weaknesses will enable the North Atlantic alliance to firmly and

appropriately meet the challenge it now faces, neither

overreacting nor underreacting. Some refer to the Russian

challenge as “Soviet Union 2.0.”10 However,

that overstates and misapprehends the challenge. To understand

the challenge Russia presents and why it is not “Soviet Union

2.0,” we must understand the roots of the challenge in the Cold

War and the collapse of the USSR.

I. THE COLD WAR

To understand the Cold War we must understand

Russia and the Soviet Union; to understand the Soviet Union we

must understand Marxism. Thus, we start our inquiry with an

examination of Marxism, then the Soviet Union, and finally the

transformation from cold war to cold peace. This inquiry

proceeds in historical order.

A.Marxism

The Cold War was driven in theory by a

pervasive and irreconcilable ideological conflict between

liberal individualist capitalism versus collectivist

authoritarian socialism. To understand the Soviet Union and why

the Russian Federation is not “Soviet Union 2.0,” we must

understand Marxist theory. Although Marxist ideology drove the

USSR, Marxist thinking is remarkably absent in the ideology of

Putin’s United Russia party. We examine Marxist theory first

from the economic base, which is the foundation of the

ideological

9.Volodymyr

Valkov, Expansionism: The Core of Russia’s Foreign

Policy, NEW E. EUR. (Aug. 12, 2014), http://www.neweasterneurope.eu/articles-and-commentary/1292-expansionism- the-core-of-russia-s-foreign-policy.

10.See

Charles Clover, Clinton Vows

to Thwart New Soviet Union, FIN. TIMES (Dec. 6, 2012) http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a5b15b14-3fcf-11e2-9f71-00144feabdc0.html (“There is a move to re-Sovietise

the region.” (quoting U.S. Secretary of State Hillary

Clinton)).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

101

|

superstructure in Marxist thought. After

understanding Marxist economics, we then look at the Marxist

ideological superstructure built on that base11

in order to understand the USSR as the precursor and

predecessor state to the Russian Federation.

1.Marxist

Economic Theory

According to Marxism, history follows

progressive development through successive stages in a

dialectical spiral12 of class

conflict: thesis versus antithesis leading to their synthesis at

a higher level of systemic order. Marx believed the numerous

social classes in history had been reduced by economic progress

to a bi-polar zero-sum conflict

between capitalists and workers.13 Marxism

holds that capitalism, with its inevitable economic cyclicity,

fosters warfare to obtain access to resources, to increase market-share,

and to employ the unemployed.14 Marx

predicted the inevitable collapse of advanced capitalist

economies in revolution due to ever-greater

economic cyclicity: economic boom, panic, depression, and war.15 For Marxism, the inevitable

tendency of capitalism is to monopolize16

because of brutal zero-sum competition:

each capitalist wishes to destroy his

or her competitor, legally if possible, illegally if necessary.17 Per Marx, capitalists are driven into

destructive competition in order to obtain a larger market-share

and more profits, even without “rent seeking,” though rent

seeking also motivates brutal and destructive competition.18 Economies of scale, entry costs, and

specialization are other factors that push capitalism toward

monopolizing.

11.Often,

when people analyze Al-Qaeda they note

that the name Al-Qaeda means base. Most analysts

recognize the name as referring to Al-Qaeda as

originally a database of Mujahadeen and not as a reference to

Marxist theory of the productive base and the ideological

superstructure, or for that matter of Maoist theory of guerilla

zones and guerilla base areas.

12.See

JEAN RIVERO,

LES LIBERTÉS PUBLIQUES 87–88 (1974) (“In

addition, Marxism is historical materialism. It believes that

man and society are at every moment, a reflection and product of

history and of the dialectical movement behind it. In this

perspective the existence of permanent rights, given once and

for all, and removed the movement of history, is obviously

unacceptable. Like all the laws, ‘human rights’ are only a

reflection of the economic infrastructure. The expression of the

power of the ruling class, and the means for it to impose its

domination the exploited classes.”) (unverified source).

13.See

KARL MARX

& FRIEDRICH ENGELS, THE COMMUNIST MANIFESTO 25–26 (D. Ryazanoff ed., Eden Paul & Cedar Paul

trans., Russell & Russell 1963) (1848).

14.See

id.

15.See

1 KARL MARX, CAPITAL: A CRITICAL

ANALYSIS OF CAPITALIST

PRODUCTION 455– 58

(Frederick Engels ed., Samuel Moore & Edward Aveling

trans., Int’l Publishers Co. 1947) (1867).

16.IAN

WARD, INTRODUCTION

TO CRITICAL LEGAL

THEORY 116 (2d ed.

2004) (citing Marx for the proposition that the natural

tendency of capitalism is to monopolize).

17.See

id.

18.See

id.

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

102

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

Monopoly is terrible, per Marxism, because

oligarchs can exploit workers who are essentially helpless in

the face of concentrated economic power.19 This

essential weakness of the exploited individual explains Marxist

skepticism toward individualism. To Marx, “individual freedom”

is not just the freedom to starve and be homeless while

unemployed; it is also the paralysis of any effort to

collectively organize the exploited so as to defend themselves

from concentrated economic power.20

History shows that the Malthusian predictions

of Marxism—ever greater market cyclicity leading

to global war and revolutions—are mostly

inaccurate. Marxists underestimated the power of technological

innovation and legal rationalization to reform capitalism out of

deep depression and wars for markets and resources. Capitalism

reformed itself out of self-destructive global

wars for markets and resources in the post-war

social democratic era due to the spate of social democratic

legal reforms enacted to forestall another great depression and

prevent another world war. The U.N., NATO, the EU, the UDHR,21 ICCPR,22 ICESCR,23 CERD,24 CEDAW,25 GATT,26 IMF,

27 IBRD,28 as

well as bank insurance (FDIC),29 unemployment

insurance, health insurance, and national pension plans such as

social security were all intended to prevent another economic

depression, mass unemployment, and consequent world war.

Although the Malthusian predictions of Marxism proved false, the

19.See

ANTHONY BREWER, MARXIST THEORIES

OF IMPERIALISM: A CRITICAL

SURVEY 50– 51 (2d

ed. 1990).

20.See,

e.g., MICHAEL A. LEBOWITZ, BEYOND

CAPITAL: MARX’S POLITICAL ECONOMY

OF THE WORKING CLASS

122–23

(2d ed. 2003).

21.Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217 (III) A, U.N.

Doc. A/RES/217(III) (Dec. 10, 1948), available at http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/.

22.International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted and opened for signature, ratification

and accession Dec. 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171, available at http://www.ohchr.org/

en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx.

23.International

Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, adopted and opened for signature, ratification

and accession Dec. 16, 1966, 993 U.N.T.S. 3, available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx.

24.International

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial

Discrimination, adopted and opened

for signature and ratification Dec. 21, 1965, 660

U.N.T.S. 195, available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CERD.aspx.

25.Convention

on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against

Women, adopted and opened for

signature, ratification and accession Dec. 18, 1979,

1249 U.N.T.S. 13, available at http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm.

26.General

Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Oct. 30, 1947, T.I.A.S. No.

1700, available at http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/gatt47_e.pdf

(forerunner to the World Trade Organization).

27.INT’L MONETARY FUND, http://www.imf.org

(last visited Oct. 13, 2014).

28.INT’L BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION

& DEV., http://go.worldbank.org/SDUHVGE5S0

(last visited Oct. 13, 2014).

29.FED. DEPOSIT INS. CORP., http://www.fdic.gov

(last visited Oct. 13, 2014).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

103

|

Marxist prediction of a natural tendency of

capital to monopolize seems accurate because monopolistic

production is generally more efficient.30 Nevertheless,

capitalist economies do not feature ever more extreme and ever

more rapid economic cyclicity (hysteresis) triggering global war

and global revolution, at least not since 1945.31 Capitalism in the developed world

seems to have mostly tamed the business cycle and to have

definitively de-linked economic cycles from war

for markets and resources: the 2008 great recession did not

unleash any war among the developed countries, at least not so

far.

2.Marxist

Legal Theory

Marxism argues that the economic base, the

material conditions of production, generally determine the

ideological superstructure, and that the ideological

superstructure merely justifies and rationalizes the relations

of productive forces.32 Marxism sees

private property as the final mechanism of oppression and a

source of separation between men.33 To

Marx the state is merely the executive committee of the

bourgeoisie.34 Capitalist law, per

Marxism, is purely formal,35 an

illusion,36 which justifies

exploitation by a dominant class over a dominated class.37 Thus, Marx wanted to abolish the state

and its laws. Consequently, Marxist legal theory is

fundamentally antinomian.38 None of

this is part of United Russia’s worldview, but partly explains

why Russia has difficulty forming itself as a rule of law state.

30.See

BREWER, supra

note 19, at 24.

31.See

Steve Keen, Is Capitalism

Inherently Unstable?, PIERIA (Apr. 29, 2013),

http://www.pieria.co.uk/articles/is_capitalism_inherently_unstable.

32.See

KARL MARX, A CONTRIBUTION TO THE CRITIQUE

OF POLITICAL ECONOMY

20 (Maurice Dobb ed., S.W. Ryazanskaya trans.,

1970).

33.JEAN-MARIE

PONTIER, LIBERTÉS

PUBLIQUES 136

(1997).

34.MARX & ENGELS,

supra note 13, at 28.

35.JEAN-JACQUE

VINCENSINI, LE

LIVRE DES DROITS

DE L’HOMME 186

(Robert Laffont ed., 1985) (“For Marxists, these freedoms are

essentially ‘formal’ in the sense that they would be empty of

any real substance, and therefore, pure form.”).

36.Eric

Engle, Human Rights According to

Marxism, 65 GUILD PRAC. 249, 255 & n.10 (2008) (“Civil

rights are merely the rights of the bourgeoisie.” (quoting PHILOSOPHISCHES WORTERBUCH

780 (Georg Klaus & Manfred Buhr eds., 1974))).

37.JEAN

ROCHE & ANDRÉ

POUILLE, LIBERTÉS

PUBLIQUES 11 (11th

ed. 1995).

38.EVGENY

BRONISLAVOVICH PASHUKANIS, THE GENERAL THEORY OF LAW & MARXISM

61 (Chris Arthur ed., Barbara Einhorn trans.,

Transaction Publishers 2002) (1978) (“The withering away of

certain categories of bourgeois law (the categories as such, not

this or that precept) in no way implies their replacement by new

categories of value, capital and so on.”).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

104

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

B.The

Soviet Union

1.Soviet

Law

Having understood the basics of Marxist

economics, we can now proceed to try to understand the USSR. We

examine Soviet law to understand some of the reasons why

contemporary Russia has difficulty forming a rule of law state.

a.Antinomianism

in Soviet Law

The basic problem facing Soviet law was the

fact that its teleology was the dissolution of the state into

society. Antinomianism undermined the concept of the rule of law39 in the Soviet system: Why build the

rule of law if the objective of state power and the inevitable

trend of history is the transformation of state power into

social peace? Furthermore, for Pashukanis, the leading Soviet

legal theorist, the rule of law is a mirage used to delude the

working class.40 Thus, “socialist

legality,”41 the attempt to implement

the formal rule of law42 to govern

ordinary transactions of daily life43 in

the USSR, was doomed from the start due to dictatorship,44 the absence of separation of powers,45 political purges,46

and a reign of systematic terror47 during

both the

39.Kazuo

Hatanaka, The “Rule of Law” State Notion in the USSR

and the Eastern Europe—A Comparison with the

Japanese Constitutional Experience, RITSUMEIKAN L. REV., March 1991, at 1, 1

(“A generally accepted definition of the rule of law is that

in order to protect the rights and freedoms of the people, the

state power should be exercised under the objective law which

is based on the will of the people.”).

40.PASHUKANIS, supra note

38, at 146.

41.Hatanaka,

supra note 39, at 7 (“[T]he

concept of socialist legality originally included the observance

of the law and other legal norm by the people, as its essential

component.”); Pierre Lavigne, La Légalité

Socialiste et la Développement de la Préoccupation Juridique

en Union Soviétique, REVUE D’ETUDES COMPARATIVES EST-OUEST,

Sept. 1980, at 5, 8–14.

42.Hatanaka,

supra note 39, at 4–5

(“[Socialist legality is] a principal of strict observance and

exact exercise of constitution, laws and other acts by all state

organ, public servants, social organization and citizen.”).

43.The

Law of Nov. 30, 1918: On the People’s Courts, Collection of

Laws of RSFSR, 1918, No. 85, art. 22 (noting that People’s

Judges must decide on written law; lacunes to be covered via

“revolutionary legal conscience”).

44.See

Karl Marx, Marx to J.

Weydemeyer, March 5, 1852, in KARL MARX & FREDERICK

ENGELS: SELECTED WORKS IN ONE VOLUME 679,

679 (9th prtg. 1986) (“[T]he class struggle necessarily leads to

the dictatorship of the proletariat . . . [and] this

dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the

abolition of all classes and to a classless society . . . .”

(quoting Marx in a letter to J. Weydemeyer in New York)).

45.Id.

at 291 (“The Commune was to be a working, not a

parliamentary, body, executive and legislative at the same

time.”); KONSTITUTSIIA SSSR (1936) [KONST. SSSR] [USSSR CONSTITUTION]

arts. 35, 59, 67, 81, 91.

46.But

see Harold J. Berman, Principles

of Soviet Criminal Law, 56 YALE L.J. 803, 805

(1947) (containing no reference whatsoever to the trials of

1936 and 1937).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

105

|

Lenin48 and Stalin

eras, which literally put the nails into the coffin of the rule

of law, as shown by the execution of Pashukanis himself—among

thousands of others. This history makes clear why Russia has

difficulty attaining the rule of law to this day.

b.Human

Rights to Soviet Law

Marxist legal theory, though antinomian, is

not without teleology. Marxism seeks to subordinate the state to

society and ultimately replace the state with society in order

to end exploitation and war.49 Marx

saw capitalist human rights as progress relative to feudalism.50 Marx regarded human rights as

necessary for the achievement of socialism.51

Marxist human rights laws are collective52 social claims of all persons to

substantive goods, subject however to the limitations imposed by

the material facts and contextualized by history53

47.Id.

(“[T]he courts should not do away with

terror—to promise that would be to deceive ourselves and others—but

should give it foundation and legality, clearly, honestly,

without embellishments.” (quoting 27 LENIN, COLLECTED WORKS

296 (3d ed. 1932))); N.V. KRYLENKO, LENIN ON COURTS

111 (1927).

48.Resolution

of Council of People’s Commissars of Sept. 5, 1918, Collection

of Laws of RSFSR, 1918, No. 710 (noting that enemies of the

state are to be imprisoned; if necessary, shot). See also White Terror, IZVESTIA,

Sept. 5, 1918, at 1.

49.KARL

MARX, CRITIQUE

OF THE GOTHA PROGRAMME

31 (C.P. Dutt ed., 1933).

50.Engle,

supra note 36, at 254 &

n.1 (“Already in his ‘On the Jewish Question’ Marx had proven

that the so called Human rights are class rights—political

emancipation is a great step forward but only progress within

the exploitative society.” (quoting PHILOSOPHISCHES

WORTERBUCH 780 (Georg Klaus

& Manfred Buhr eds., 1974))).

51.Id.

at 251–52; see also PHILOSOPHISCHES WORTERBUCH

782 (Georg Klaus & Manfred Buhr eds., 1974) (“Human

rights are necessary for the transition from capitalism to

socialism.”) (unverified source).

52.Engle,

supra note 36, at 254 &

n.1 (“The goal of socialist civil rights is neither absolute

individualism or the loss of the individual within the masse.

Rather, fundamental rights contribute to the formation of all-round

developed harmonious persons.” (quoting PHILOSOPHISCHES

WORTERBUCH 783 (Georg Klaus

& Manfred Buhr eds., 1974))).

53.As

Frederick Engels wrote:

Freedom does not consist in the dream of

independence from natural laws, but in the knowledge of these

laws, and in the possibility this gives of systematically making

them work towards definite ends. This holds good in relation

both to the laws of external nature and to those which govern

the bodily and mental existence of men themselves—two

classes of laws which we can separate from each other at most

only in thought but not in reality. . . . Freedom therefore

consists in the control over ourselves and over external nature,

a control founded on knowledge of natural necessity . . . . The

first men who separated themselves from the animal kingdom were

in all essentials as unfree as the animals themselves, but each

step forward in the field of culture was a step towards freedom.

FREDERICK ENGELS, ANTI-DÜHRING 157

(2d ed. 1959).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

106

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

and the finality of the socialist

construction: the abolition of law and the state54 and the replacement of the state with

society.55 Early soviet legislation

was consequently very open textured, seeking to exhort56 and educate,57 to

teach the masses to read,58 to

participate in political discourse, and to grow as

54.EVGENY

B. PASHUKANIS, LAW

AND MARXISM: A GENERAL

THEORY 61 (Chris

Arthur ed., Barbara Einhorn trans., 1978) (“The withering away

of certain categories of bourgeois law (the categories as

such, not this or that precept) in no way implies their

replacement by new categories of proletarian law, just as the

withering away of the categories of value, capital, profit and

so forth in the transition to fully-developed socialism will not mean the emergence of new

proletarian categories of value, capital and so on. The

withering away of the categories of bourgeois law will, under

these conditions, mean the withering away of law altogether,

that is to say the disappearance of the juridical factor from

social relations.”).

55.See

ROCHE & POUILLE,

supra note 37, at 27 (“The freedoms

of 1789 are linked to the capitalist regime, the freedoms of the

rich.”).

56.Csaba

Varga, Lenin and Revolutionary Law-Making, in COMPARATIVE LEGAL

CULTURES 515, 516

(Csaba Varga ed., 1992) (“The main features typical of

revolutionary legislation are its very general nature, the fact

that the laws and statutory instruments frequently take the form

of an appeal or a proclamation or a declaratory character or a

statement of principle, the wording of the clauses, which is

clear, fluid and direct, and the often almost total liberty of

structure, to be noted in particular in the lack of separation

between the ‘whereas’ clauses and the legal provisions. In

general, such legislation has the character of an instrument of

revolutionary propaganda designed to stimulate and educate,

partly because of the language and structure adopted for the

norms; in other words—to quote an expression of Lenin’s—it

suffers from the ‘formal imperfections’ which characterize the

sort of norms which scarcely meet the requirements of

professional jurists.”).

57.26

V.I. LENIN,

Report on the Activities of the Council of People’s

Commissars January 11 (24), in COLLECTED WORKS 455, 464 (George Hanna ed., Yuri Sdobnikov &

George Hanna trans., 1964) (“[W]e transformed the court from

an instrument of exploitation into an instrument of education

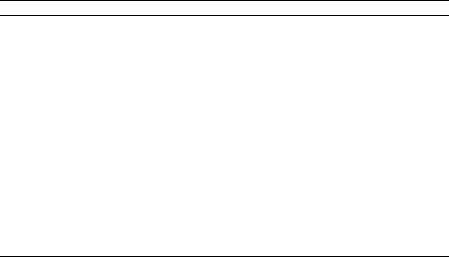

. . . .”).

58.N.

BUKHARIN & E. PREOBRAZHENSKY, THE ABC OF COMMUNISM 293 (Eden

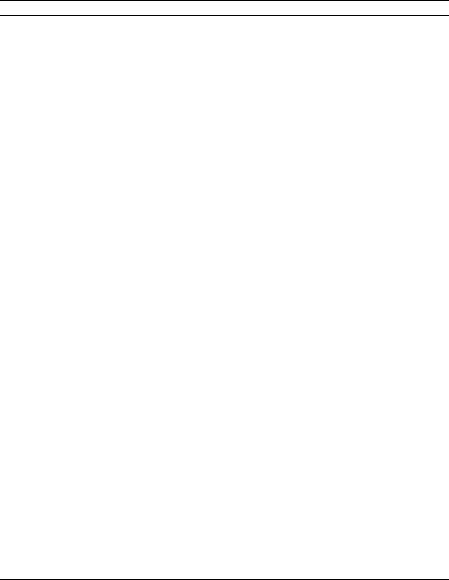

Paul & Cedar Paul trans., 1969). The following graph

demonstrates the efforts towards literacy:

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

107

|

individuals in society.59 The

Soviet concept of human rights as hortatory claims of groups to

collective resources entailing workers’ rights to housing,

shelter, and medical care are different from the legally binding

civil and political rights of the Anglo-American

concept of human rights. This may partly explain why protecting

basic human rights in Russia remains difficult even today.

c.The

Soviet State

To understand the cold war, we must understand

the Soviet state. The USSR was a one-party system,

a workers’ and peasants’ dictatorship in name,60

directed and led by the Communist Party of the Soviet

Union (CPSU). The CPSU regarded itself as a vanguard party, the

most advanced elements (intelligentsia) of the most advanced

class (the proletariat), subject to democratic centralism and

exercising a dictatorship on behalf of the proletariat (workers

and peasants).61 The CPSU was a

centralized, hierarchical party of elites directing a centrally

planned economy via dictatorship.62 The

party elite

Dynamics of Literacy 1897–1979:

Population

Aged 9–49, in Percentages

|

Population

|

|

1897

|

1920

|

1926

|

1939

|

1959

|

1970

|

1979

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rural

|

M

|

35.5

|

52.4

|

67.3

|

91.6

|

99.1

|

99.6

|

99.6

|

|

|

F

|

12.5

|

25.2

|

35.4

|

76.8

|

97.5

|

99.4

|

99.5

|

|

|

All

|

23.8

|

37.8

|

50.6

|

84.0

|

98.2

|

99.5

|

99.6

|

|

Urban

|

M

|

66.1

|

80.7

|

88.0

|

97.1

|

99.5

|

99.9

|

99.9

|

|

|

F

|

45.7

|

66.7

|

73.9

|

90.7

|

98.1

|

99.8

|

99.9

|

|

|

All

|

57.0

|

73.5

|

80.9

|

93.8

|

98.7

|

99.8

|

99.9

|

|

Total

|

M

|

40.3

|

57.6

|

71.5

|

93.5

|

99.3

|

99.8

|

99.8

|

|

|

F

|

16.6

|

32.3

|

42.7

|

81.6

|

97.8

|

99.7

|

99.8

|

|

|

All

|

28.4

|

44.1

|

56.6

|

87.4

|

98.5

|

99.7

|

99.8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Narodnoe

obrazovanie, nauka i kul’tura v SSSR: Statisticheskii sbornik (Moscow, 1977), 9; SSSR i zarubezhnye

strany, 1987: Statisticheskii sbornik (Moscow,

1988), 83.

59.Varga,

supra note 56, at 519

(“Lenin’s theory of the need for legislation to be general in

character was intended to be applicable only during a transition

stage, and carried with it the requirement that the subsequent

legislation, based on an appraisal of past experience and making

provision for specific matters, should be more directly

dependent on the practical results achieved and on the

political, social and technical experience acquired in the

course of the enforcement of existent laws in a creative

manner.”).

60.KONSTITUTSIIA SSSR (1936) [KONST. SSSR] [USSSR CONSTITUTION]

art. 1 (“The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is a socialist

state of workers and peasants.”).

61.See

Eric Engle, From Russia with

Love: The EU, Russia, and Special Relationships, 10 RICH. J. GLOBAL L. & BUS. 549, 551 (2011).

62.Id.

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

108

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

of the CPSU (the “nomenklatura”) claimed to

govern on behalf of and for the benefit of the workers and

peasants, i.e. the peoples of the Soviet Union, to obtain the well-being

of the workers and peasants63 and to

prevent the wars for market share that capitalism unleashed in

economic crises at the trough of business cycles.64 The USSR, following Marx’s

prescription to transform the state into civil society,65 sought to end market relations

entirely66 to attain the goal of

peace and prosperity. The dictatorship of the party on behalf of

the workers and peasants was justified as necessary to work

revolutionary changes on their behalf.67 The

initial performance of the USSR was in fact remarkable. The CPSU

ended famine and illiteracy68 that

characterized Tsarist Russia69 in the

USSR, doubling the average life expectancy70

despite purges and a world war that in total killed about

twenty million Soviet citizens.71 Leninism

also instituted sex equality.72 In

real human terms, such as average life expectancy and literacy

rates, Leninism was unquestionably progress as compared to

Tsarism.

Over time however, the Soviet system

degenerated and increasingly worked to the benefit of the party

establishment (the “nomenklatura”)73 at

the expense of the broad masses of workers and peasants.

Meanwhile, the threat of

63.KONSTITUTSIIA SSSR (1977) [KONST. SSSR] [USSSR CONSTITUTION]

art. 1 (“The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is a socialist

state of the whole people, expressing the will and interests of

the workers, peasants, and intelligentsia, the working people of

all the nations and nationalities of the country.”).

64.See,

e.g., V.I. LENIN, STATE AND REVOLUTION

5 (Int’l Publishers 1932) (1917); V.I. LENIN, WHAT IS TO BE DONE: BURNING QUESTIONS

OF OUR MOVEMENT 54–55 (Victor J.

Jerome ed., Joe Fineberg & George Hanna trans., Int’l

Publishers 1969) (1902); MARX, supra note 15; MARX

& ENGELS, supra note 13, at 42–54.

65.See

FREDERICK ENGELS, SOCIALISM: UTOPIAN

AND SCIENTIFIC 68

(Andrew Moore ed., Edward Aveling trans., Mondial 2006)

(1880).

66.See,

e.g., KONSTITUTSIIA SSSR

(1936) [KONST. SSSR] [USSSR CONSTITUTION] art. 4 (“The socialist system

of economy and the socialist ownership of the means and

instruments of production firmly established as a result of the

abolition of the capitalist system of economy, the abrogation of

private ownership of the means and instruments of production and

the abolition of the exploitation of man by man, constitute the

economic foundation of the U.S.S.R.”).

67.Engle,

supra note 61.

68.Id.; see also Boris N.

Mironov, The Development of Literacy in Russia and the

USSR from the Tenth to the Twentieth Centuries,

31 HIST. EDUC. Q. 229, 243

(1991).

69.Engle,

supra note 61; see also Jeff Coplon, In Search of a Soviet

Holocaust: A 55-Year- Old Famine Feeds the Right, VILLAGE VOICE, Jan. 12, 1988, at 30.

70.Engle,

supra note

61; see also STEPHEN WHITE, RUSSIA GOES DRY: ALCOHOL, STATE,

AND SOCIETY 43 (1996).

71.THE

CONCISE OXFORD

DICTIONARY OF POLITICS

466 (Iain McLean ed., 1996).

72.See

Engle, supra note 61, at 552;

see also GAIL WARSHOFSKY LAPIDUS,

WOMEN IN

SOVIET SOCIETY: EQUALITY, DEVELOPMENT, AND

SOCIAL CHANGE

136 (1978).

73.Engle,

supra note 61, at 552; see also MICHAEL VOSLENSKY, NOMENKLATURA:

THE

SOVIET RULING CLASS 240–45

(Eric Mosbacher trans., 1984).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

109

|

invasion diminished. From this perspective,

which I call dual de-legitimation, we can better

understand the sudden, unexpected, and relatively bloodless

restoration of capitalism74 in

Russia. The system, in its own terms,

lost legitimacy as being no longer necessary (defense against a

war which never came) or effective (consumer well-being

was simply higher in the West, and the nightmare of Tsarist

famine, illiteracy, and inequality was long past). These

systemic facts help explain the near bloodless dissolution of

the Soviet system.

2.Soviet

Economics

a.The

Planned Economy

The Soviet planned economy succeeded at

shifting the USSR from a semi- feudal economy facing literal

starvation and illiteracy producing but a score of basic goods

into an industrial economy. However, the newly created

industrial economy produced a myriad of different goods.75 This production diversity doomed the

centrally planned economy: an ever-greater variety

of products made central planning increasingly complex and thus

less efficient at coordinating production and consumption. The

result was suboptimal economic performance.76

The USSR’s centrally planned economic production system

was more appropriate for a semi-feudal

industrializing society with few goods than for a highly

developed industrial economy producing a myriad of goods.77 As to the promised workers’ paradise,

leisure was assured, but consumer goods were always in short

supply.78 Quality of goods suffered

from production deadlines at the end of the five-year

planning cycles when

74. Capitalism is a system of economic

production predicated on the private ownership of capital. It is

distinct from state capitalism wherein capital is held by the

state or through public- private partnerships. Capitalism is

also defined as an industrial rather than a feudal mode of

production. The Tsarist economy was semi-feudal

and industrializing. Further, many of its economic projects

involved heavy state participation (state capitalism). However,

the ownership of capital in the hands of a financial elite

distinguishes Tsarist semi-feudal (state)

capitalism from the Soviet planned economy. Of course, strong

state participation in the economy, directly and indirectly,

remains a mark of the Russian economy. However, private

ownership of capital and the role of the Orthodox Church as

spiritual guide of the nation were definitively restored in the

post-Soviet era. Thus I refer to this process as

“capitalist restoration” rather than “capitalist instauration.”

See, e.g., Engle, supra

note 61, at 552; see also STEVEN ROSEFIELDE,

COMPARATIVE ECONOMIC SYSTEMS: CULTURE, WEALTH, AND POWER IN

THE 21ST CENTURY

183(2002).

75.See

Eric Engle, A Social-Market

Economy for Rapid Sustainable Development, GUJARAT NAT’L L. U. J.L. DEV. & POL., Dec. 2009, at 42,

42–55.

76.See,

e.g., WORLD BANK, BELARUS: PRICES, MARKETS, AND ENTERPRISE REFORM

1

(1997).

77.See

LUDWIG VON MISES, ECONOMIC CALCULATION

IN THE SOCIALIST

COMMONWEALTH 4 (S.

Adler trans., 1990).

78.See

Engle, supra note 61, at 568;

see also Robert Whitesell, Why Does the Soviet Economy Appear to be

Allocatively Efficient?, 42 SOVIET STUD. 259, 260–68 (1990).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

110

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

production goals had to be met.79 In sum, the quality of Soviet life did

not match Western European standards. This was mostly because so

much of the government’s resources were wasted on building a military-industrial

complex that did not advance the well-being of

Soviet citizens.80

b.Autarchy

The Soviet leadership sought to create

socialism in one country81 via

economic autarchy.82 While

historically justified by Russia’s history of invasion after

invasion, autarchy is suboptimal to trade. This, along with the

inefficiencies of the planned economy, partly explains the

collapse of the Soviet Union.

Pursuant to the policy of autarchy, a ruble

currency economic zone was created—and the ruble

with official exchange rates, not market rates.83 Capital restrictions were the norm.84 So were border controls such as

customs duties and passport checks.85 Autarchy

complemented military security by enabling independent political

choices.86 The Soviet leadership saw

military security as a precondition to economic security and well-being.87 To

circumvent the problem of a lack of foreign currency and the

inability to use the ruble for currency exchanges overseas and

related problems arising from the nature of a closed economic

system, barter in and for real goods was taken up by and between

the COMECON countries. For example, the USSR would barter with

Cuba, trading sugar for finished Soviet goods, a practice known

as countertrade.88 Barter also

occurred at the micro-economic level, though not

as a legitimate de jure instrument of state policy, but as a de

facto necessity of

79.See

Engle, supra note 61, at 568; see also Zigurds L. Zile, Consumer Product Quality

in Soviet Law: The Tried and the Changing, in

2 SOVIET LAW AFTER STALIN: SOCIAL

ENGINEERING THROUGH LAW 183,

202 (Donald D. Barry et al. eds., 1978) (explaining the rising

quality of Soviet goods between the 1960s and 1970s).

80.See

Engle, supra note 75.

81.J.V.

STALIN, The

October Revolution and the Tactics of the Russian Communists, in

PROBLEMS OF LENINISM 117, 121

(1976).

82.Ronald

A. Francisco, The Foreign Economic

Policy of the GDR and the USSR: The End of Autarky?, in EAST GERMANY IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

189, 190 (David Childs et al. eds., 1989).

83.Engle,

supra note 61, at 554.

84.Id.

85.Id.

86.Id.

87.Id.

88.Engle,

supra note 61, at 554; see also José F. Alonso & Ralph J.

Galliano, Russian Oil- For-Sugar

Barter Deals 1989–1999,

in 9 CUBA IN TRANSITION 335, 335 (1999).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

111

|

everyday life, albeit of questionable

legality.89 “Gifts” however could be

justified as a “social” and “fraternal” act under the Marxist

logic of transforming monetary economic compulsion into

cooperative voluntary social acts.90 However,

with capitalist restoration, the primitive version of a “gift

economy” became warped into generalized bribery, undermining the

rule of law in the post-Soviet era.91

Preferential tariff treatment for the COMECON

and Soviet client states was a key feature of the international

trade policy of the Socialist bloc.92 High

tariff barriers were created to protect the autarchic COMECON

home market.93 These tariff barriers

would also encourage infant industries. Non-tariff

technical barriers such as restrictions on imports for health

and safety reasons also served the logic of autarchy.

Intellectual property would be either unprotected or weakly

protected in order to use Western innovation to support the

USSR.94 Software piracy of Western

computer technology software and microchip technology was the

norm during the Soviet era95 and

intellectual property law enforcement in Russia remains a sore

spot to this day.96 The centrally

planned economy aimed to accumulate the surplus capital needed

for economic development through the creation of infrastructure

(e.g., housing,

89. Engle, supra note 61, at 554–55; see also JIM LEITZEL, RUSSIAN REFORM 128 (1995); Byung-Yeon

Kim, Informal Economy Activities of Soviet

Households: Size and Dynamics, 31 J. COMP.

ECON. 532, 545 n.24 (2003).

90.Engle,

supra note 61, at 555.

91.Id.

92.

Id.; see

also MARIE LAVIGNE, INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL

ECONOMY AND SOCIALISM

174–75 (David Lambert trans.,

1991); ADAM ZWASS,

THE COUNCIL FOR MUTUAL ECONOMIC

ASSISTANCE: THE THORNY PATH FROM POLITICAL

TO ECONOMIC INTEGRATION

8 (1989).

93.Engle,

supra note 61, at 555. COMECON

(also known as the CMEA) was the USSR’s effort to form a common

market within the Soviet bloc. See, e.g.,

JENNY BRINE,

COMECON: THE

RISE AND FALL OF AN INTERNATIONAL

SOCIALIST ORGANIZATION, at xvi (1992).

94.Engle,

supra note 61, at 555.

Intellectual property remains but is weakly protected in the

Russian federation and the USSR successor

states. As noted by the European Union Commission:

[C]ounterfeiting and piracy activity in Russia

remains on a high level. The lack of effective enforcement

affect Russian markets on a large scale. To be fully integrated

in the world trading system, to continue to attract foreign

investment and to prevent major losses for right-holders,

Russia has to implement all its international obligations, in

particular the ones related to Intellectual Property Rights and

their Enforcement.

Directorate-General for Trade, Intellectual Property: Dialogues, EUROPEAN COMM’N, http://ec.

europa.eu/trade/creating-opportunities/trade-topics/intellectual-property/dialogues/#_russia

(last visited Apr. 4, 2012).

95. Engle, supra note 61,

at 555; see also Shane Hart, Computing

in the Former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe,

CROSSROADS,

March 1999, at 23, 23–25.

96. Engle, supra note

61, at 555–56; see also REPORT ON THE PROTECTION

AND

ENFORCEMENT OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

RIGHTS IN THIRD

COUNTRIES, EUROPEAN

COMMISSION 17

(2013), available at http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2013/march/tradoc_1

50789.pdf.

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

112

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

roads, airports) via forced saving97 and also, more ominously, for military

production in order to wage war.

C. The Cold War

As seen, there were essential fundamental

differences between individualist capitalist liberalism and

Marxist dictatorship. These ideological and economic differences

manifested in the Cold War. The Cold War was characterized by

constant conflict, overt and covert. Arms control was a

perennial political issue of the Cold War to prevent or limit

the arms race, and arms control remains a key issue with respect

to Russia today.98

The U.S. and U.S.S.R. expressed their Cold

War conflicts through proxy wars, most notably in Korea,

Vietnam, Israel, and Afghanistan, as well as in dozens of

smaller conflicts over several decades.99 State-sponsored

terrorism was also a feature of the Cold War. The admitted

examples are the U.S. funding of anti-Marxist

rebels in Nicaragua (Contras) and Mujahadeen in

Afghanistan,100 but

it is fairly obvious that groups such as the Red Brigades, the

Japanese Red Army, and the Red Army Faction,101

as well as the

Palestinian Liberation Organization, obtained

covert funding, covert weapons deliveries, and covert training

by the USSR102 and/or China

(including the inter-Marxist conflict via covert

action in the ZAPU, ZANU, and ANC). In the background was the

constant threat of atomic war, and this is likely to feature in

the cold peace. Each system sought to avoid such a war through

the UN, alliance networks, and diplomacy, yet both were based on

a military industrial complex, which fostered the conflict.

Geopolitically, the Soviet system can be

described as a series of concentric rings. At the center was the

USSR, then Eastern Europe,103 then

Third World

97.For a detailed explanation of the import

substitution industrialization model in the context of Soviet

development theory, see Engle, supra

note 75.

98.Shannon

N. Kile, Mar. 10: Making a New START in Russian-U.S.

Nuclear Arms Control, STOCKHOM INT’L PEACE RES. INST., http://www.sipri.org/media/newsletter/essay/

march10 (last visited Oct. 17, 2014).

99.Julia

Gallivan, U.S. Proxy War Policy During the Cold War, INTRO TO GLOBAL SEC. (Feb. 26, 2013, 2:10 AM), http://introglobalsecurity.blogspot.com/2013/02/us-proxy-war-policy- during-cold-war.html.

100.Steve Galster, Afghanistan: The Making of

U.S. Policy, 1973–1990, NAT’L SEC. ARCHIVE (Oct. 9, 2001), http://www2.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB57/essay.html.

101.Nick Lockwood, How the Soviet Union

Transformed Terrorism, THE ATLANTIC (Dec. 23, 2011,

8:30 AM), http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/12/how-the-soviet- union-transformed-terrorism/250433/.

102.Andrew Campbell, Moscow’s Gold: Soviet

Financing of Global Subversion, NAT’L

OBSERVER, Autumn 1999,

at 19, 19–20.

103.See JOSEPH G. WHELAN & MICHAEL

J. DIXON, THE

SOVIET UNION

IN THE THIRD WORLD: THREAT TO WORLD

PEACE? 7–9 (1986).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

113

|

Marxist states, and finally Third World non-Marxist

allies.104 The closer a country was

geographically to the Soviet center, the greater the level of

integration into the autarchic economy. Western efforts to

“rollback” Marxism were generally unsuccessful,105 perhaps because the Soviet system was

autarchic. The failure of “rollback” ultimately led to the

“Brezhnev doctrine,” wherein the USSR declared the attainment of

“socialism” in any country as irreversible.106

Russia today, incidentally, has no such global network,

only regional partners in its defensive alliance the Collective

Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).107

The U.S. response to the failure of rollback

and the Brezhnev doctrine was to compete in fields where the

USSR could not compete due to technological inferiority or its

structure as a closed dictatorship; prominent examples were

computers and telecommunication.108 Consequent

to this asymmetric arms race, the USSR and its Warsaw Pact

allies wasted almost all their surplus production on

unproductive military spending,109 trying

to make up for quality differences with quantity, just as Russia

today tries to use nuclear weapons to compensate for its

technological inferiority. The U.S. aimed to bankrupt the USSR

by forcing it into an unsustainable arms race, a policy that

worked110— and in my estimate would

work again. The arms race was most evident in the Strategic

Defense Initiative (SDI or “Star Wars”) which sought to create a

missile shield against the USSR.111 The

SDI certainly violated the spirit of the since-abrogated

Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty and probably

the letter of the treaty as well.112 The

U.S. also funded anti-Soviet insurgencies, most

104.Engle, supra note

61, at 553.

105.See PETER GROSE, OPERATION ROLLBACK: AMERICA’S SECRET WAR BEHIND THE IRON

CURTAIN 210 (2000).

106.See MATTHEW J. OUIMET, THE RISE AND FALL OF

THE BREZHNEV DOCTRINE

IN SOVIET

FOREIGN POLICY 1–3, 6 (2003).

107.Richard Weitz, Moscow’s

Afghan Endgame, HUDSON INST. (June 25, 2014), http://www.hudson.org/research/10399-moscow-s-afghan-endgame.

108.See Engle, supra note

61, at 557.

109.Russian Military Budget, GLOBAL SECURITY, http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/

world/russia/mo-budget.htm (last visited Oct. 16,

2014) (“By the mid-1980s, the Soviet Union devoted

between 15 and 17 percent of its annual gross national product

to military spending . . . .

Until the early 1980s, Soviet defense

expenditures rose between 4 and 7 percent per year.”). See

also ANDERS ÅSLUND, BUILDING CAPITALISM: THE TRANSFORMATION

OF THE FORMER SOVIET

BLOC 131 (2002).

110.1 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE COLD WAR 862–63

(Ruud van Dijk ed., 2008) (unverified

source).

111.4 CATHAL J. NOLAN, THE GREENWOOD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INTERNATIONAL

RELATIONS 1600

(2002).

112.See Donald G. Gross, Negotiated

Treaty Amendment: The Solution to the SDI–ABM

Treaty Conflict, 28 HARV. INT’L L.J. 31, 31–32 (1987).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

114

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

evidently in Afghanistan and Nicaragua.113 The economic strains on the Soviet

system, which resulted from the arms race and proxy wars, led to

constant shortages that seriously undercut the USSR’s claim to

be creating a workers’ paradise with the highest standard of

living for ordinary people on earth.114 “The

party of Lenin,” despite initial success, was ultimately unable

to match capitalism in the quality and abundance of consumer

goods.115 This, coupled with the

increasing tendency of the nomenklatura to serve its own

interest rather than to seek the well-being of all

the Soviet peoples and the fact that the U.S. was not in fact

threatening to invade the USSR to seize resources, led to a

crisis of purpose, a crisis of legitimacy, and capitalist

restoration resulting in chaotic and often criminal

privatization.

II.FROM

COLD WAR TO COLD PEACE

A.Economic

Collapse and Corruption

The collapse of the USSR was marked by chaos,

corruption, and economic failure116 and

was followed by asset stripping and mafia wars, which resulted

in declining average life expectancy

in Russia during the 1970s.117 The

U.S. at least tolerated criminal tendencies of certain Russian

classes118 if only because much

legitimate economic activity was defined as economic crime by

Soviet

113.WOLFF HEINTSCHEL

VON HEINEGG, CASEBOOK

VÖLKERRECHT § 399

(Beck ed., 2005) (unverified source).

114.31 V.I. LENIN, COLLECTED WORKS 516

(Julius Katzer ed., 1966) (“Communism is Soviet power plus the

electrification of the whole country.”). That is, the Soviet

system justified itself as the fastest route to development,

which it was for at least one generation. However, ultimately,

the system lost legitimacy as it became clearer and clearer that

the West produced better quality consumer goods and in greater

numbers.

115.See ALEX F. DOWLAH & JOHN

E. ELLIOTT, THE

LIFE AND TIMES

OF SOVIET SOCIALISM

182 (1997).

116.See Privatization: Lessons from Russia and China, INT’L LAB. ORGANIZATION, http://www.ilo.org/public/english/employment/ent/papers/emd24.htm

(last visited June 25, 2014) (“By the beginning of 1997 the

Russian economy had perhaps reached its lowest point. GNP fell

by 6 per cent [sic] in 1996, compounding a decline of more

than 50 per cent [sic] since 1991 (although the shadow economy

has expanded). Many enterprises are on the brink of collapse;

the proportion of loss-making enterprises in the main economic sectors is

approximately 43 per cent [sic].”).

117.See Donald A. Barr

& Mark G. Field, The Current State of Health Care

in the Former Soviet Union: Implications for Health Care Policy

and Reform, 86 AM. J. PUB. HEALTH 307, 308 (1996).

118.See Carlos Escude, When

Security Reigns Supreme: The Postmodern World-System

vis a vis Globalized Terrorism and Organized Crime, in TRANSNATIONAL TERRORISM IN THE WORLD

SYSTEM PERSPECTIVE 69, 85 (Ryszard Stemplowski

ed., 2002); ALFRED W. MCCOY, THE

POLITICS OF HEROIN: CIA COMPLICITY

IN THE GLOBAL DRUG

TRADE 385 (1991).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

115

|

standards:119 All Russian economic actors in the early

1990s were “criminals,” at least according to Soviet law.

B.The

Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

The CIS arose in the chaotic aftermath of the

collapse of the USSR.120 Unlike the

USSR, the CIS never had well-articulated goals.

The CIS leaders and the contending factions within and outside

of the nomenklatura lacked a unifying ideology and policy

program in the face of the literal bankruptcy of Marxism.121 Lacking a common teleology or goal,

the CIS degenerated into the political overseer of the peaceful

dissolution of the USSR122 and, to a

certain extent, the introduction of market mechanisms to replace

the planned economic system. The CIS is typically described as

“moribund,”123 and it failed to

evolve into a viable transnational governing institution due to

a lack of a common vision124 and

inexperience in transnational institutionalism,125 particularly with

119.See WILLIAM A. CLARK, CRIME

AND PUNISHMENT IN SOVIET

OFFICIALDOM: COMBATING

CORRUPTION IN THE POLITICAL

ELITE, 1965–1990, at

9 (1993).

120.Michael Roberts & Peter Wehrheim, Regional

Trade Agreements and WTO Accession of CIS Countries, 36 INTERECONOMICS 315, 315 (2001) (“Shortly after the collapse of

the Soviet Union most of its successor states, with the

exception of the Baltic States, joined the Commonwealth of

Independent States (CIS). At the same time many CIS countries

opened up their trade regimes by dismantling various trade

restrictions, state trading monopolies, multiple exchange rate

regimes as well as formal tariff barriers. However, in the

course of the 1990s pressure for the protection of domestic

industries has increased. Import tariffs on ‘sensitive

imports,’ such as refined sugar, have started to pop up. By

far the most serious barriers to trade and the ones most

frequently used are non-tariff barriers. The ever more complex and constantly

changing trade regimes of many CIS countries have also opened

the door for corruption and smuggling.”).

121.STEPHEN K. BATALDEN

& SANDRA L. BATALDEN, THE NEWLY INDEPENDENT STATES

OF EURASIA: HANDBOOK

OF FORMER SOVIET

REPUBLICS 19 (2d ed.

1997) (discussing the factional conflict within the RSFSR at

formation of the CIS); Georgi M. Derluguian, The Process and the Prospects of Soviet Collapse:

Bankruptcy, Segmentation, Involution,

in QUESTIONING

GEOPOLITICS: POLITICAL PROJECTS

IN A CHANGING WORLD-SYSTEM

203, 215 (Georgi M. Derluguian & Scott L.

Greer eds., 2000) (discussing factionalism within the

nomenklatura); Boris Grushin, The

Emergence of a New Elite: Harbinger of the Future or Vestige

of the Past?, in THE

NEW ELITE IN POST-COMMUNIST EASTERN EUROPE 53,

57 (Vladimir Shlapentokh et al. eds., 1999) (discussing a lack

of vision among Russia’s political parties and their leaders).

122.Roberts & Wehrheim, supra note 120, at 323 (“Ten years after

the break up of the USSR, CIS countries are still struggling to

find the appropriate format to govern their mutual trade

relations. At present a patchwork of half-implemented

bilateral agreements and a series of paper framework agreements

govern intra-CIS trade relations. Most of the RTAs

among CIS member states remain de jure agreements.

If one were to characterise this institutional framework, one

might term it ‘managed disintegration.’”).

123.See Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), GLOBAL SECURITY, http://www.global security.org/military/world/int/cis.htm

(last visited Oct. 20, 2014).

124.Joop de Kort & Rilka Dragneva, Department

of Economics Research Memorandum 2006.03: Russia’s Role in

Fostering the CIS Trade Regime 9 (Leiden

Univ. Dep’t of Econ. Res.

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

116

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

regards to market liberalization126 and the rule of law. Moreover, some

of the new managerial class were Soviet era “economic

criminals,”127 while others were

former nomenklatura. The CIS’s failure is unsurprising, and was

perhaps even inevitable given those conditions.128 Lacking a common vision, the CIS

defaulted into the role of the clearinghouse for the USSR’s

remarkably peaceful dissolution via two distinct factors: (1)

privatization, and (2) the devolution of former federal powers

to individual Republics.129

The institutional problems mentioned

contributed to the breakdown of CIS. For example, the CIS’s

transnational trade policy was characterized by incoherence.

Numerous overlapping multilateral and bilateral treaties covered

similar issues,130 leading to

economic disputes due to the contradictory obligations imposed

by the various treaties. However, these overlapping multilateral

and bilateral treaties also left many issues unaddressed.131 For example, the CIS’s agreements

were not sophisticated enough to take into

Memorandum 2006.03), available

at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1440809

(“The CIS was burdened with ambivalent goals. On the one hand,

it aimed to assist the newly independent countries to gain

economic independence, while on the other hand it was the

intended institution to bring the newly independent states

together in an economic union. The ambivalent character of the

CIS, and the increasing self-consciousness, both

politically and economically, of the newly independent states,

resulted in numerous bilateral and multilateral agreements at

the same time.”).

125. See Margot Light, International Relations of Russia and the

Commonwealth of Independent States,

in EASTERN

EUROPE AND THE COMMONWEALTH

OF INDEPENDENT STATES

64, 65 (2d ed. 1994).

126.Philip Hanson, The

Economics of the Former USSR: An Overview, in EASTERN EUROPE

AND THE COMMONWEALTH OF INDEPENDENT STATES, supra note 125, at 43, 43.

127.See, e.g., Leonard

Orland, Perspectives on Soviet Economic Crime, in SOVIET LAW AND

ECONOMY 169, 169

(Olimpiad S. Ioffe & Mark W. Janis eds., 1987); Charles A.

Schwartz,

Economic Crime in the U.S.S.R.: A Comparison

of the Khrushchev and Brezhnev Eras, 30 INT’L

COMP. L.Q. 281, 281–82

(1981).

128.Nonetheless, its failure was remarkable in that

it contributed to the peaceful transition from one-party

dictatorships to independent republics with varying degrees of

democratic participatory government. See Stephan

Kux, From the USSR to the Commonwealth of

Independent States: Confederation or Civilized Divorce?,

in FEDERALIZING EUROPE?: THE

COSTS,

BENEFITS, AND PRECONDITIONS OF FEDERAL

POLITICAL SYSTEMS

325, 325 (Joachim Jens Hesse & Vincent

Wright eds., 1996).

129.Id. at 346–47. See

also Stephan Kux, Confederalism and

Stability in the Commonwealth of Independent States, 1 NEW EUR. L. REV. 387, 390–91 (1993).

130.de Kort & Dragneva, supra note 124, at 1 (“What can be

observed in the CIS is that economic cooperation takes the form

of overlapping bilateral and multilateral agreements of very

distinct legal quality. From an economic point of view it does

not make sense that countries that have concluded a multilateral

free trade agreement, as the CIS countries did in 1994, an

agreement that they amended in 1999, subsequently conclude

bilateral free trade agreements with their partners as well. It

creates overlap, it increases transaction costs, and it

obfuscates the status of both the multilateral and bilateral

agreement.”).

131.Id. (“The agreements that are concluded

often are partial and selective, while their ratification and

implementation also is a mixed affair . . . .”).

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

2014]

|

A NEW COLD WAR? COLD PEACE. RUSSIA,

UKRAINE, AND NATO

|

117

|

account non-tariff trade

barriers such as health, safety, and technical restrictions to

trade.132 Ultimately, conflicting

rules, gaps in rules coverage, and non-enforcement133 gutted

the CIS treaties of efficacy, created legal uncertainty, and

increased transaction costs.134 The

CIS’s institutions and rules were simply ineffective.135 The CIS states were unable to

effectively implement transnational trade governance due to

incoherent rules, absent institutionalism, and corruption.

Lacking effective rules and institutions, a political approach

predominated, which only further impeded any effort by the CIS

partners to maintain productive synergies such as a customs

union, a common currency, and common health and safety

standards. Moreover, the frequent use of reservations by CIS

member states rendered the agreements pointless, impeding legal

stability from taking root in CIS institutions.136

Any effort to bring the USSR’s customs and

monetary union into the CIS era was thus doomed for several

interlocking reasons. There was an absence of useful legal

concepts such as “basic economic rights” (the four freedoms)137 as a necessary means to the desirable

end of economic integration to obtain peace and prosperity. The

absence of legal concepts in the CIS treaties, such as

subsidiarity, proportionality, and acquired community positions

(acquis communautaire),138 further crippled the CIS because

those are methods of coordinating supranational and

intergovernmental tendencies in order to attain

132.Id. at 3 (“The CIS trade regime can be

described as a symbiosis between bilateral and multilateral

regimes, both of which can be described as weak regimes.

Bilateral agreements cover some key free trade rules, such as

tariffs, but remain minimal and quite basic. Non-tariff

barriers, for instance, are generally left out, as are

liberalisation of services or intellectual property to name a

few issues that have become important in international trade

agreements. Disputes are generally resolved through

consultations.”).

133.Roberts & Wehrheim, supra note 120, at 319 (“Though most CIS

countries have FTAs with each other on a bilateral basis, not

all of them are practically implemented or enforced.”).

134.de Kort & Dragneva, supra note 124, at 2 (“[F]ragmentation

poses a danger of rule clashes, patchy implementation, and a non-transparent

and complex administration of the regime.”).

135.Id. at 1 (“[Ninety] per cent [sic] of all

multilateral documents that create the legal base of the CIS,

and there are more than 1,000 of them, are ineffective.

According to many observers, the CIS seems to have failed in

becoming an effective framework of economic cooperation and

(re)integration.“).

136.Id. (“[T]he CIS applies the ‘interested

party’ principle, which implies that a state could choose not to

participate in a certain agreement or decision without

afflicting its validity.”).

137.The central concept to the foundation of the

European Union as an economic area is the four freedoms (basic

rights): the free movement of goods, workers, capital, and

enterprises among the Member States. See Eric Engle, Europe

Deciphered: Ideas, Institutions, and Laws, FLETCHER

F. WORLD AFF., Fall 2009, at 63, 75.

138.Knud Erik Jorgensen, The Social

Construction of the Acquis Communautaire: A Cornerstone of the

European Edifice, EUR. INTEGRATION ONLINE PAPERS, Apr. 29, 1999, at 1, 2, available at http://eiop.or.at/eiop/pdf/1999-005.pdf; Acquis Communautaire,

BBC NEWS (Apr.

30, 2001, 11:52 AM), http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/europe/euro-glossary/1216329.stm.

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY

SCHOOL OF LAW

|

118

|

SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY LAW JOURNAL

|

[Vol. 59:97

|

by accretion the objectives of economic

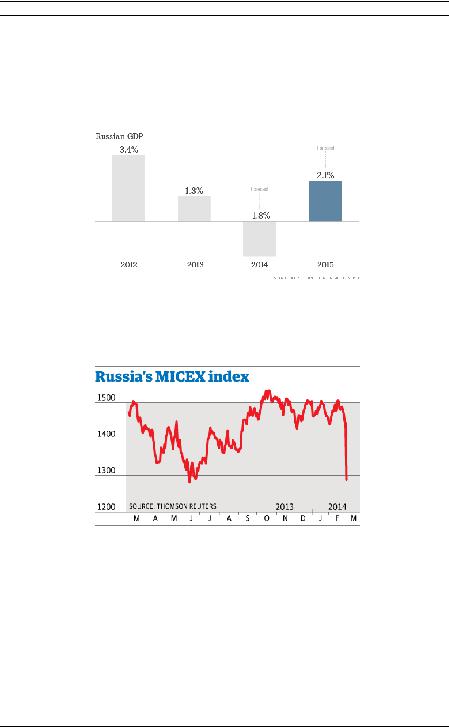

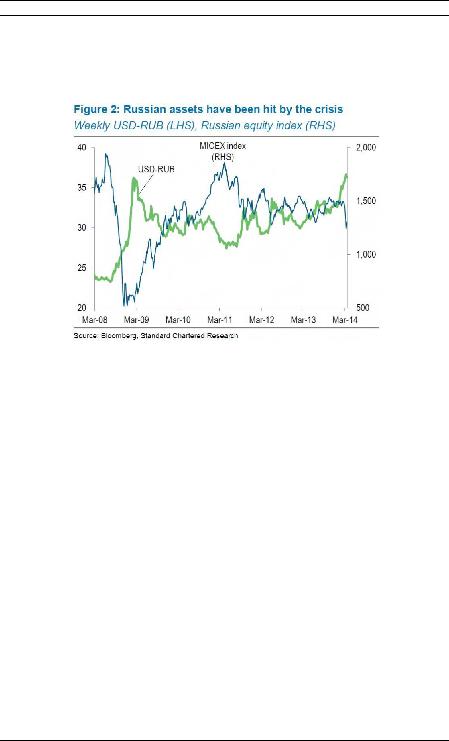

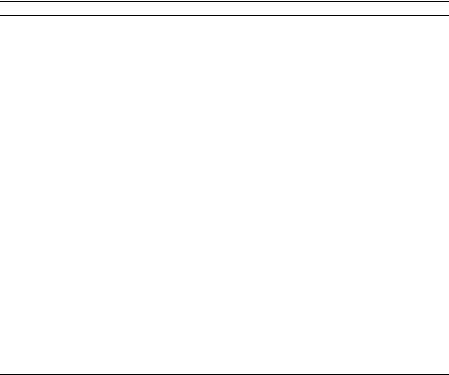

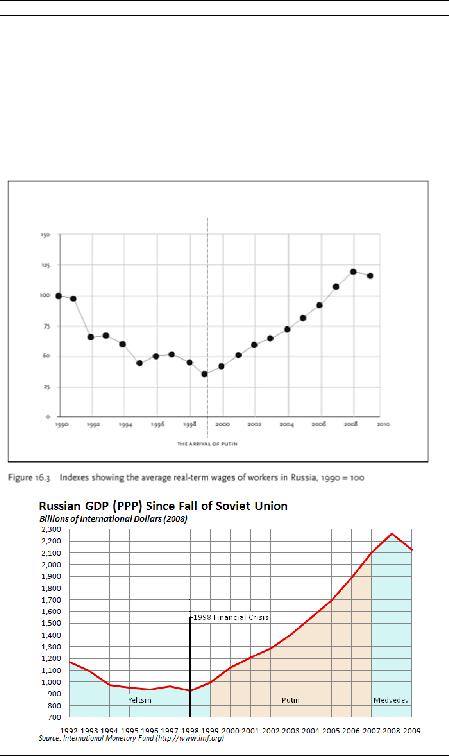

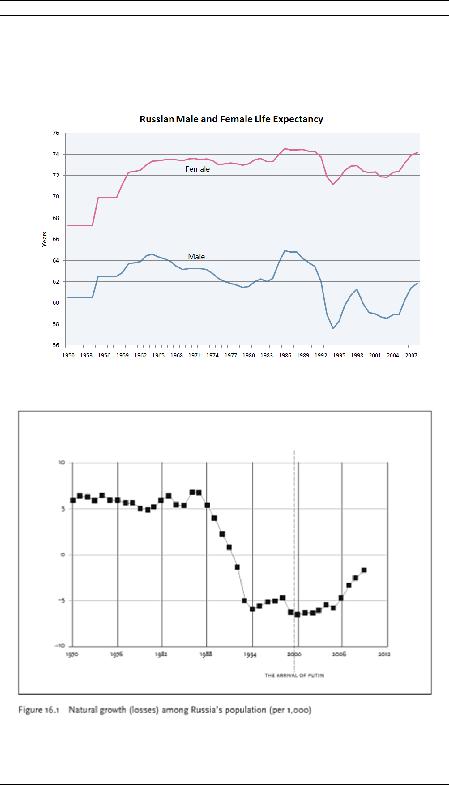

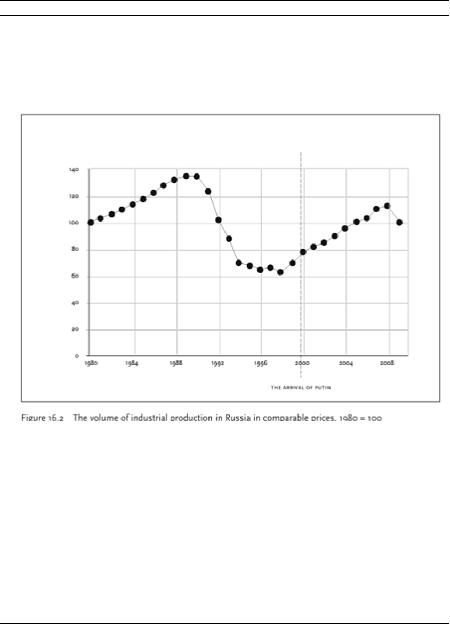

integration.139 Finally, common